Jamie McKinley

Arresting the toughest offender

The daughter of a bailiff, Jamie McKinley spent a lot of time in courthouses, watching trials.

“I was probably like 15 or 16, and in the summer I remember not wanting to make lunch, so I would go to my mom’s work and make her take me to lunch, and I would sit in on the cases all the time,” says McKinley, whose mother worked in Ohio’s Portage County Municipal Court system.

Jamie McKinley, a police officer at The University of Akron, arrested one of life's toughest offenders — cancer .

McKinley was fascinated by criminal cases and crime scene investigations. She devoured “true crime” books and television shows, wanting to get inside the heads of criminals, to understand their motives and methods.

“I knew at age 16 that I wanted to be a police officer,” she says. “I just said to my mom, ‘I’m going to the academy.’”

After graduating from Field High School, McKinley went to The University of Akron (UA), where she earned her associate degree in criminal justice and joined the UA Police Academy at age 21. She graduated from the academy at 23 and was hired by the UA Police Department two years later.

“I still looked like a college kid, so on my very first day on the job, they threw me on campus with a backpack and gave me a picture of a guy and said, ‘Look for him,’” she says. “I didn’t even know how to talk on the radio …. Eventually the other officers got him and arrested him.”

Over time, McKinley matured into a respected patrol officer, specially trained to collect evidence at crime scenes – dusting for prints, reconstructing shootings, sending items to lab for testing.

One day she responded to a call that shots had been fired near the Polsky Building. A man in a delivery truck said he was robbed and shot at.

McKinley canvassed the scene. Something was off, she thought.

The next day, the police department received notice that a bullet casing had been found on the ground at the scene. McKinley remembered there had been snow on the ground. She would have noticed a casing dropped in the snow. She examined her photos again. There had been no casing.

It was later discovered that the driver had returned to the scene to place the casing on the ground, where he alleged the shooter had been. It turned out that the only shooter was the driver himself, who had accidentally fired his gun in his truck and lied about the robbery afterward.

McKinley wasn’t surprised. She had seen just about everything in her years on the force.

But in late 2016, an unusual set of facts began to emerge, culminating in a confrontation with a new kind of adversary.

- Fact one: McKinley was unaccountably tired. Very tired. A short walk on campus left her breathless.

- Fact two: Her neck hurt. It hurt so bad that the pain rushed down her back like a tortuous river of flame.

Her investigation produced the following:

- Exhibit A: a softball-sized tumor next to her heart, which may have been there for a year or two, the doctor said.

- Exhibit B: excessive fluid in the sac surrounding her heart – a condition called “pericardial effusion.”

- Exhibit C: a collapsed lung.

The samples were sent for testing, and the silent suspect – who all this time had been lurking in the dark cavity of her own chest, like a foe hidden in the heart of campus – was caught red-handed, poisons spilling through his fingers.

Cancer, the doctor said. Specifically, Hodgkin lymphoma.

Only once, McKinley says, did she cry. Oddly enough, it was at the thought that there would be no one to do her daughter’s hair in the morning.

“She wanted her hair done every morning before school,” McKinley says, “and I remember thinking, ‘Who’s going to do her hair? My husband can’t do it right.’ It was one of those weird things you think about as a mother.”

The thought of her children – five and seven years old at the time – weighed heavily on her.

“They feed off you, so if you’re upset and concerned, they’re going to be upset and concerned,” McKinley says. “So I slept during the day, but made sure that I was up, awake, and on the couch when my kids came home, so they didn’t realize how sick I was.”

She knew that the cancer, if she let it, would – like that bullet casing placed on the ground – divert her attention. It would make her think of herself and her misery, and distract her from her husband and children, and the need to remain strong for them.

She would call the cancer’s bluff. She would pay no attention to his misdirections and traps, the intimidations whispered in the night, the daily threats and alarms.

She would, in fact, look him in the face, and laugh.

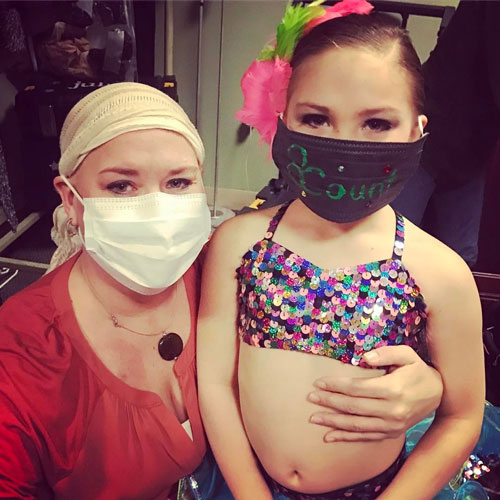

“I began losing my hair from the chemo, and it was so thin that we decided to throw a party,” McKinley says. “We all shaved our heads. My brother, his son, my husband, my son – I wouldn’t let my daughter, though – and we had our friends come over. My girlfriend’s a photographer, and she came and took pictures. My other girlfriend’s a hairdresser, so she came over and let my kids shave my head. They tried to get me to wear a mohawk. They thought it was cool. It was super fun, and we all laughed.”

Later, when McKinley went to pick out a wig with her friend and her mom, they had so much fun taking selfies and trying on all the reds, blacks and blondes that an employee was not sure how to react.

“The poor lady that was sizing me was not really sure what to think – we were hooting and hollering and making jokes,” McKinley says. “They actually asked me to be their spokesperson. They did a whole interview and commercial, and I was on their webpage and pamphlets – they loved that I was so outgoing and fun about it.”

Earlier, while she was in the hospital, fellow police officers would visit, including one officer who, when McKinley first started complaining about pain in her neck, advised her to drink as much water as possible, thinking it was a pinched nerve.

When he came into the room, McKinley, having recently learned about the excessive fluid around her heart, cried out, “Dude, you tried to drown me! I drank all that water like you said!”

“Why did you listen to me? I don’t know!” he replied.

For McKinley, such jocularity was one of the best ways to disarm, and finally apprehend, her offender.

“I just chose to have fun with it – as much fun as one can have,” she says. “I was super positive. I tried to make the best out of the situation. … My kids and I laughed at what we could, we watched movies and hung out. It was nice to spend time with them.”

After five months and 12 rounds of chemotherapy, and then a month of daily radiation treatments, McKinley received her first cancer-free scan shortly before Thanksgiving in 2017.

She returned to work and resumed normal activities, including participating in the annual Christmas with a Cop event, where local police officers treat around 100 children to breakfast, a cruise down down Market Street – complete with lights and sirens – and a shopping spree at the Walmart in Fairlawn.

Making children smile and beating cancer – it’s all in a day’s work for Officer McKinley. It’s just a matter of collecting evidence, acting on it, and making the world a safer place.

“I don’t know that I’ve done anything super amazing or ‘empowering,’” she says. “I just did what I had to do.”